The phrase “you are what you eat” was first coined by a nutritionist named Victor Landlahr for a 1923 beef advertisement in a Bridgeport, CT newspaper. Ironically, this household saying originated at a time when American food was becoming increasingly processed, and less of an ideal basis for a healthy self image. For the better part of 22 years, my own red meat and high fructose corn syrup-heavy diet, punctuated by cravings for McDonald’s, has been far from perfect, and is a sad reflection of the poor dietary standards seen across the United States. Eating habits form early in life, and while many factors contribute to the staggering 20% obesity rate among American children, one often criticized ingredient is school lunch in America, which, high in carbs, often low in nutrition, and coupled with easy access to sugary drinks in vending machines makes for a lot of unhealthy and not so genki (lively) kids.

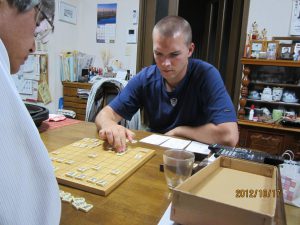

As Nanae’s English teacher, I enjoy the rare privilege of eating school lunch with my students every day. There are many noticeable differences between school lunch in Concord and Nanae besides the food itself, and these differences apply to greater Japan as well. For one, there are no cafeterias in Nanae’s elementary and middle schools. Students eat lunch together in their class with their teacher, and students serve the lunch. There is a rotating shift of classroom duties that students take on, from first grade through ninth, including chalkboard cleaning, trash collection, and serving kyuushoku. Every day at noon, a half dozen students in each class put on white aprons, cafeteria caps and the classic Japanese face mask to dish out the lunch to every student and teacher. After everyone’s seated, we put our hands together as if in prayer and say “Itadakimasu!” and it’s time to eat. Eating in the classroom and self service saves a ton of money. When you build a school in Japan, you can skip the cafeteria. Also, rather than each school employing kitchen staff and servers, the students do the serving and the food preparation for all of Nanae’s 8 elementary and 3 middle schools is done at a single facility.

CLICK HERE TO SEE MY 26 FAVORITE SCHOOL LUNCHES!

The Nanae kyuushoku center is a relatively small building tucked away behind Nanae Elementary, Nanae’s second biggest elementary school, located in the center of Honcho (downtown). Today I spoke with the center’s head nutritionists (with the translating aid of CIR Senpai Ben Haydock), Mmes. Matsumoto and Ichimura. Together they plan out Nanae’s kyuushoku on a monthly basis.

Unlike in Concord, kyuushoku is only served in elementary and middle schools. Nanae high schoolers are on their own, either bringing a lunch from home or buying food from a small bento (Japanese-style lunch box) store in the school. The Nanae kyuushoku center cooks lunch for 2,400 students and teachers Monday through Friday. In elementary school, parents are billed 230 Yen per lunch, about $2.25, and 270 Yen ($2.66) in the middle school. For this low price, students get a bowl of rice three times a week and a bread roll twice weekly, a carton of milk from an Onuma dairy farm, a bowl of soup, a vegetable or fruit dish, and a main protein-heavy course, usually meat or fish. The kyuushoku milk, like nearly all milk in Japan, is whole milk (3.5%). It may seem strange that a country with such lean people consumes almost only whole milk, but whole milk might be getting an unfair rap in the states. A recent study in the European Journal of Nutrition actually concluded that there is an inverse relationship between whole milk consumption and obesity amongst test subjects in Europe. Like Japan, the European diet relies on less processed food and a lower daily caloric intake than in the states, so a glass of whole milk a day might actually be good for you provided you’re not dunking twelve Oreo’s in it.

Matsumoto says that when planning the daily kyuushoku for each month, she and Ichimura look for a balance between a) what the kids like, b) what the school wants them to eat, and c) what meals might not be available at home, either because they take a long time to prepare or because the meal is foreign in origin. For school lunches with a foreign theme, Matsumoto says that they are constantly brainstorming new ideas, and draw their inspiration for foreign menus from the internet as well as Nanae’s sister city. Ichimura says that they often talk to folks at the Kyoikuinkai (board of education) about the foods eaten in Concord and Boston, and try to replicate some of the sister city’s meals. Of the Boston cuisine replicas I’ve tried in kyuushoku, clam chowder was by far the tastiest success, but for some students it remains an acquired taste. As for catering to the students’ preferences, Matsumoto and Ichimura each make daily visits to Nanae elementary and middle school, respectively, to get feedback from students. They also conduct a twice yearly student survey to gauge the most and least popular foods.

Every day, twelve staff members cook enormous batches of kyuushoku from 7:30 a.m. until late morning, when two trucks deliver the food, by now divided into different sized metal containers individually labeled to designate a class section, to each of the eight elementary and three middle schools in town. I was hoping to be able to photograph an Olympic pool sized rice cooker when I visited the kyuushoku center, but due to the sheer volume of rice needed to serve 2,400 students and teachers, Nanae contracts with a nearby bakery that cooks up enormous batches of rice. I’m a big fan of kyuushoku rice, more so than the rice I make in my own cooker, and the reason is a simple cooking tip for all you rice lovers out there. The bigger the batch of rice you make, the more evenly it will cook, so many Japanese households tend to cook large batches of rice and then freeze what’s left for future meals.

Nanae is home to a great deal of farms featuring a whole range of produce and, season permitting, local ingredients in school lunch take preference over food from elsewhere. The head of Nanae’s farming cooperative determines which farmer will be contracted on a given day to provide the lunch center with scallions, eggs, apples, onions, mushrooms, daikon (Japanese radish), or turnips on a rotating basis. Matsumoto says that the farming community in Nanae works closely with the lunch center and is very helpful in providing local foods. A great deal of the chicken, pork and beef in kyuushoku also comes from Nanae farms, and the only frozen food you’re ever going to see is the froyo.

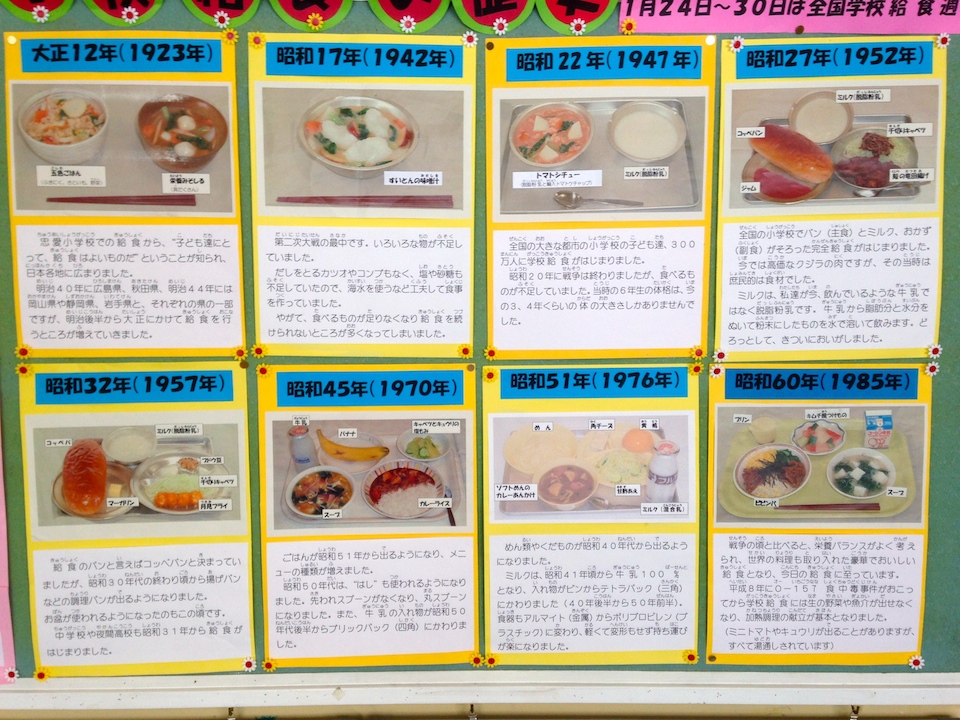

Students at Ikusagawa Elementary recently made a poster showcasing the evolution of Nanae kyuushoku over the last century. Certain dates stand out, such as 1942, during which time there was a significant food shortage. Though the school lunch in 1985 doesn’t appear much different than today, I was interested to learn how school lunch had changed since the nutritionists themselves were students. For Ichimura, as a child growing up in Nanae, the nutrition standards for school lunch were less strict, and while many more of the meals were Japanese rather than gaikoku (foreign) themed, there was a great variety amongst the basic ingredients, including the rice dishes and soups. Today, while the structural layout is less diverse; always milk, a main dish, a soup, and bread or rice, the international variety is far greater.

This past December I gave a presentation to middle school students in Nanae showing the differences between middle school life in Concord and Japan. A good portion of this presentation highlighted the contrasts between American and Japanese school lunch. My students were particularly fascinated with the concept of choosing what to eat at lunch, be it the hot lunch of the day, a PB&J or tuna salad sandwich, even a cookie or ice cream sandwich for dessert. If a student doesn’t finish their cafeteria lunch, they throw it in the garbage and can later eat a snack that they brought from home. Or in many American schools, they can just buy a candy bar from the vending machine. These options don’t exist in Japanese schools. There is one meal, and everyone eats it. If there’s a food a student doesn’t like, they’re going to learn to like it, because in Nanae learning to try new foods is a part of being a student. And if one doesn’t finish their lunch, they’ll have to wait on snacks until they get home because there are no vending machines. But I rarely see a plate with leftovers.

Matsumoto and Ichimura say they do everything possible to minimize food waste. Every day, each school’s uneaten food is collected and returned to the lunch center, where the waste is weighed before being composted. It’s been a few years since I ate American school lunch, but I don’t remember much food being recycled.

I have lived in Nanae for seven and a half months now. Each day brings a flurry of new information and cultural oddities, and the more Japanese language I pick up, the swifter this flurry becomes, and the more my understanding of Japanese customs and traditions deepens. That said, Japan is not a perfect country. There are times when I find myself frustrated by aspects of daily life here; certain things just seem to run more smoothly in America. But, I would be a fool not to recognize when the opposite is also true. School lunch in Nanae, and across Japan, from the way it is made and served, to its incorporation into education and impact on students’ health and minds is a truly unique and outstanding strength that Japan has mastered, and we in the United States would do well to follow its lead.